For Kenyan Migrant Workers, the struggle for basic labour rights and social protection when they migrate to Middle Eastern countries continues.

01/05/2022

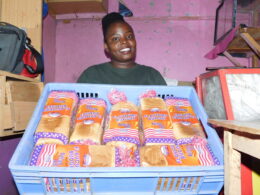

Photo of Kenyan migrant worker in Lebanon (Photo credit: Muse Mohamed)

01 May is International Workers Day also known as Labour Day for celebrating workers and workers’ rights particularly those in wage labour across the globe in various countries including Kenya. For Kenyan Migrant Workers and in particular Migrant domestic workers (MDWs), the struggle for basic labour rights and social protections in Middle Eastern countries continues.

In April 2022, Nation Africa reported that a 22 year old Kenyan woman from Trans Nzoia County by the name Stella Nafula had died reportedly from a cardiopulmonary arrest in Saudi Arabia where she was living and working as a domestic worker. Nafula’s family has been left in extreme distress over the demise of their daughter who had only been working in Saudi Arabia for 8 months. Until April 2022, the family has been unsuccessfully trying to liaise with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the respective embassy to expedite the repatriation of their daughter’s body. Nafula’s story is sadly not uncommon.

Over the last decade, numerous stories of Kenyan MDWs dying in suspicious circumstances abroad have been reported on Kenyan and International media. In September 2021, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that 90 Kenyan domestic workers died in Saudi Arabia between 2019 and 2021. It was also noted that reported distress calls for the same period were 1,908 with 883 in 2019/20 and 1,025 reported in 2020/21.

Over the last decade, numerous stories of Kenyan MDWs dying in suspicious circumstances abroad have been reported on Kenyan and International media

Many more have been reported about the abusive and exploitative conditions that MDWs continue to endure in Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Qatar, UAE and Bahrain. Due to high unemployment and underemployment rates in Kenya coupled with the demand for labour in the care and hospitality sectors in these countries, more Kenyan women are migrating abroad for better prospects. According to stakeholders, there are an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 Kenyan Migrant workers in the Middle East. Much of the recruitment is done through private employment agencies. In spite of reforms around regulations introduced by the Kenyan Ministry of Labour , many of these women end up in abusive and exploitative conditions in their employers' homes where often the only means of escape is running away. Escaping however means losing their immigration status leaving them undocumented and at risk of destitution and detention. Unable to go home and forced by their roles as breadwinners for their families, many opt to seek work in precarious freelance jobs as cleaners and carers for years.

Escaping however means losing their immigration status leaving them undocumented and at risk of destitution and detention.

Kafala, a form of sponsorship system that ties a migrant worker’s immigration and residence status to their employer has been attributed as the biggest enabling factor for the abuse and exploitation of MDWs in Lebanon and the Gulf countries. Under the Kafala, MDWs are unable to leave/change their employer or leave the country without their employer’s permission consequently trapping them in abusive situations until the end of their contracts when they’re able to return back home. The abuses that MDWs experience include confiscation of passports, long working hours with no breaks, withholding of wages, restriction of movement and communication and even physical and sexual assault. The covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges for MDWs despite care work being considered an essential service. In Lebanon, Kenyan workers were forced to camp and protest outside their consulate after losing their jobs and accommodation. In spite of the increasing coverage over the last two years of the hardships that migrant workers continue to face, there have been minimal reforms in the way of basic labour and social protections for them.

In Lebanon for example, MDWs are entirely excluded from Labour laws depriving them of the rights enshrined in these laws and others imposed by international labour conventions. These include a 48 hour limit on working hours, minimum wage ($450), annual leave, work breaks, right to terminate the contract, right to unionise, channels for employment grievances, health and safety regulations, etc. Instead, the Lebanese government attempted to impose these rights for MDWs through introducing the standard unified contract in September 2020 including right to terminate the contract with a month's notice, right to the minimum wage, right to retain the identity documents and communicate freely and a right to a healthy and safe working environment. However under this contract, MDWs are still not allowed to join and form trade unions. Furthermore, on 14 October 2020 in a case brought by the Syndicate of the Owners of Recruitment Agencies (SORAL), the Shura Council made a decision to suspend the implementation of the standard unified contract on the grounds that affording these rights to MDWs would damage the interests of the agencies. This was a severe drawback in protecting the rights and welfare of MDWs.

In Lebanon, MDWs are entirely excluded from Labour laws depriving them of the rights enshrined in these laws and others imposed by international labour conventions

On the sending end, the Kenyan government has also attempted to introduce several labour reforms to protect Kenyans working abroad. This includes establishing the National Employment Authority which is responsible for regulating private employment agencies that are responsible for recruiting Kenyans workers for foreign employment including registration and renewal of licences, inspections, safeguarding of workers, providing pre-departure training to migrant domestic workers. However, a lot more still needs to be done to strengthen NEA’s mandate to allow it to crack down on unregulated agencies that operate outside the required standards to the disadvantage of Kenyan MDWs. The Kenyan government has also negotiated various bilateral agreements with some of the labour receiving countries in the Middle East including Saudi Arabia and Qatar. However Kenyan Migrant workers based in these countries have continued to lament about poor and exploitative labour practices.

This Labour day, we stand in solidarity with Kenyan migrant workers who are driven by extreme economic precarity to immigrate for employment in countries where they are subjected to minimal labour and social protections. We call for the Kenyan Government and the labour receiving countries to put in place and implement urgent reforms to protect migrant workers including abolishing kafala, creation of channels for labour grievances, close monitoring and auditing of recruitment agencies, facilitation of repatriation and provision of reintegration support to returnees. Until Kenya provides an enabling environment for Kenyans to set up and run businesses and also create adequate employment opportunities, and until social protection is provided to those with economic insecurity, migration will remain an attractive employment option.

More stories